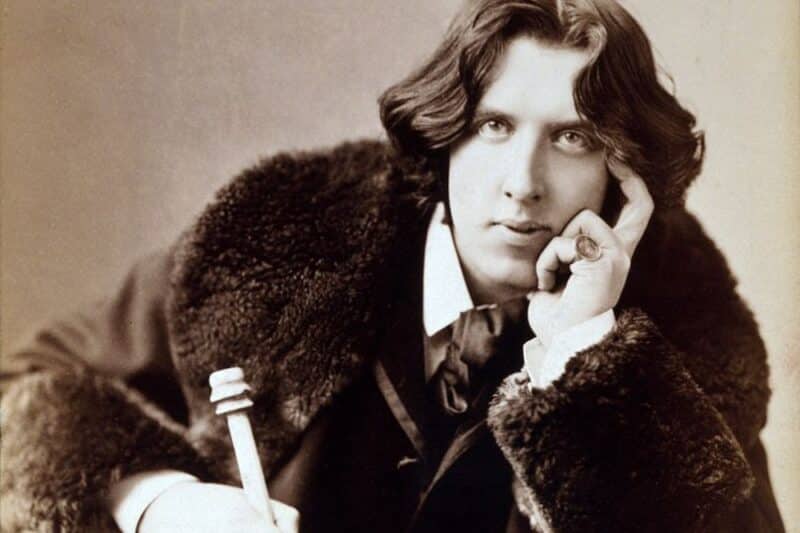

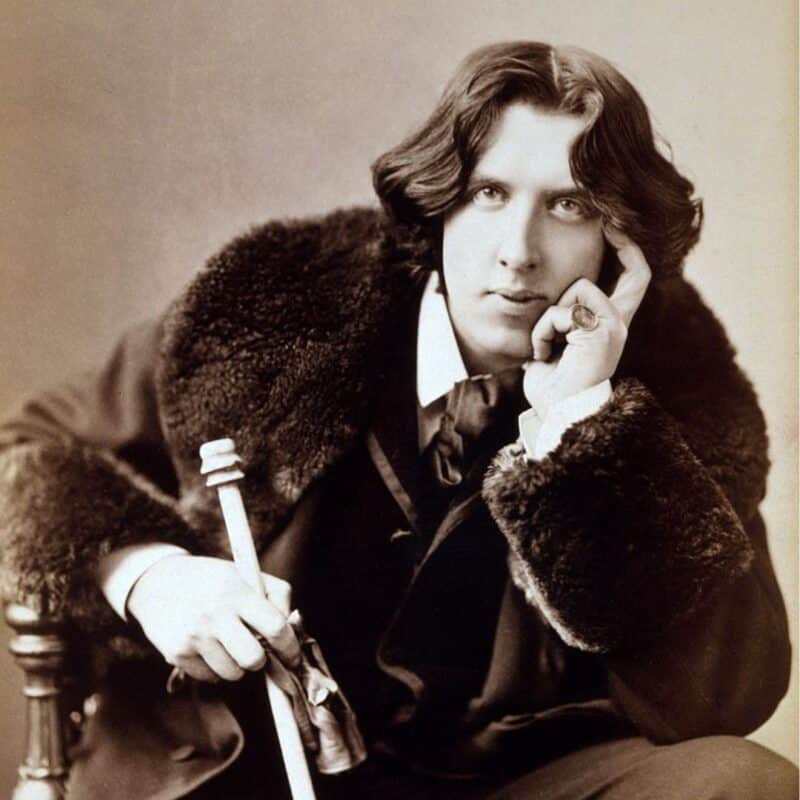

This past August marked the 141st anniversary of Oscar Wilde’s visit to the Jersey Shore. In 1882, Oscar, then a little-known artist who had only published a single, scant volume of poetry, was selected by a marketing impresario to forever change Oscar’s career. Oscar was plucked from moderate obscurity to travel across the United States for an entire year on a blistering media campaign to promote a Gilbert and Sullivan operetta. Doing so would forge the persona of “Oscar Wilde” and also bring Oscar to the Jersey Shore. Read on to Learn All About Oscar Wilde’s Time in America and the media advertising campaign that made “Oscar Wilde.”

Photo Credit: Public Domain

The name “Oscar Wilde” is so recognizably famous it’s easy to believe that it was always so as if he emerged fully formed like Athena from Zeus’ thigh. But Oscar was not always so renowned. His rise to fame was surprisingly commercial, surprisingly American — and surprisingly local. During Oscars’ long, strange journey toward immortality, he enjoyed the Jersey Shore, and the Jersey Shore enjoyed him.

Many lovers of literature lose sight of how marketing and media manipulation play a crucial role in the careers of our favorite artists. We forget that T. S. Eliot was a director in the publishing firm Faber and Gwyer (later Faber + Faber) or that Virginia Woolf published her first novel through her half-brother’s publishing house. Recently, Wilde’s unprecedented media blitz is becoming better known through a series of publications and podcasts which include the book Wilde in America: Oscar Wilde and the Invention of Modern Celebrity (published in 2014). These works shed light on Oscar’s central role in a national media advertisement campaign to promote a Gilbert and Sullivan comedic opera.

Read More: The History Behind Mermaids in New Jersey

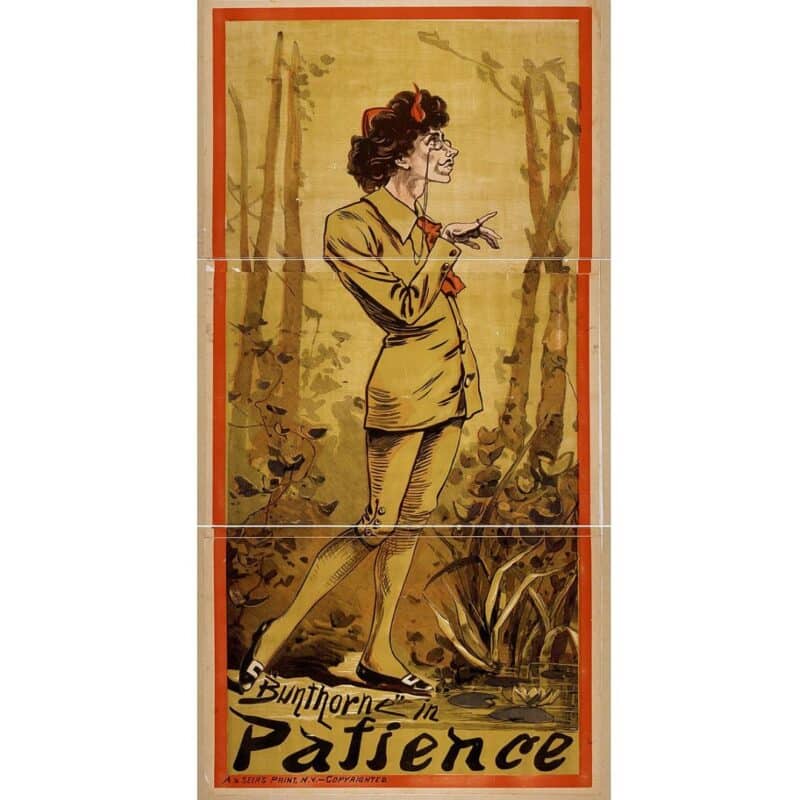

By 1881, Gilbert and Sullivan were the most famous names in English-language entertainment. One reason their operettas sold so well was because they kept material fresh by poking fun at contemporary British fads (much like South Park does today). By 1881, the leading literary fad was “Aestheticism,” a movement that celebrated beauty in the smallest, everyday items, such as wallpaper, the design of a walking cane, or the ruffles of a dress. The movement was summed up most famously as “art for art’s sake.” Gilbert and Sullivan found the movement so amusing they wrote an entire operetta devoted to lampooning the movement. The comic opera, Patience, was a smash hit in the United Kingdom.

Photo Credit: Public Domain

Naturally, if the play could expand to America, Gilbert and Sullivan (along with their financial backers) could double, even triple their earnings. The only problem was that the American public had no idea what the Aesthetic Movement was. They wouldn’t get any of the operetta’s jokes. More importantly (for the financial backers), the American public wouldn’t pay to see a show they didn’t understand. Cue Richard D’Oyly Carte and Oscar Wilde.

Photo Credit: Public Domain

Richard was a leading talent agent, theatrical impresario, and hotelier in the late Victorian Era who worked extensively to promote the works of Gilbert and Sullivan. Realizing the American public needed a patsy to better understand the operetta’s humor, Richard enlisted Oscar as the Aesthetic Movement’s “strawman”—a figure who could encapsulate the movement and bear the brunt of the operetta’s jokes.

Using Oscar to promote Gilbert and Sullivan would be like Rodgers and Hammerstein hiring Jack Kerouac to promote the Beat Movement before one of their musicals — or Trey Parker and Matt Stone hiring Amanda Gorman to lecture across America to explain the premise of the Black Lives Matter movement before a season of South Park.

Richard sent Oscar on a frenzied lecture tour across America, giving 141 lectures in only 11 months from New York to Boston, Baltimore to Cleveland, Louisville to Colorado, San Fransisco to Utah, Kansas, Nebraska, Iowa, and eventually to the Jersey Shore.

Because of his role as the Aesthetic Movement’s stooge, the press often lambasted Oscar with ridicule. The cartoonist, George Frederick Keller, makes fun of Oscar’s visit to San Fransisco by depicting Oscar as a false messiah, riding a donkey and carrying a sunflower with a money symbol:

Photo Credit: Public Domain

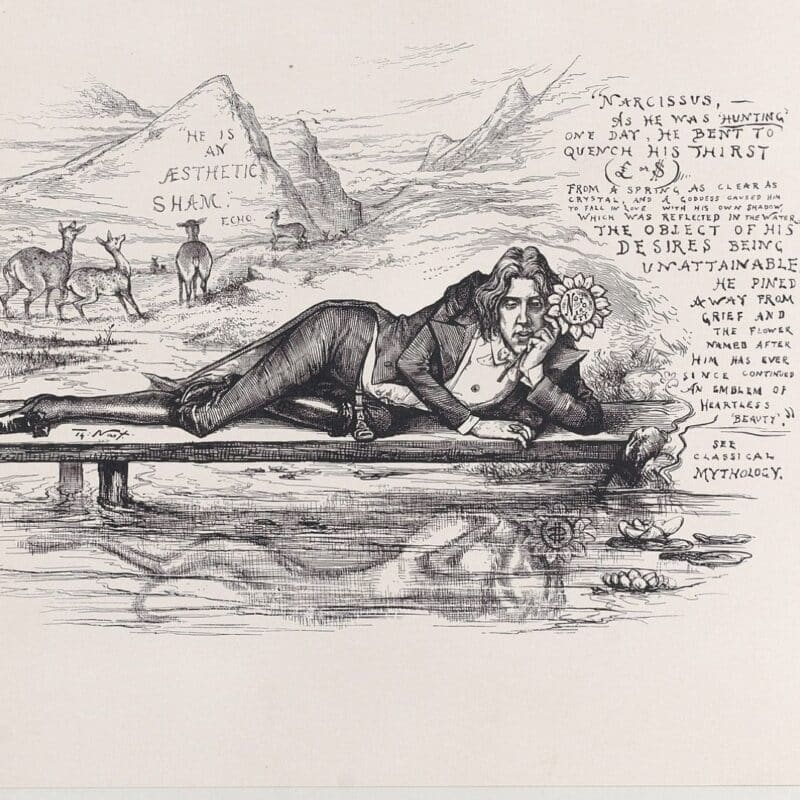

Similarly, cartoonist Thomas Nast depicted Oscar as Narcissus with the caption: “HE IS AN AESTHETIC SHAM”

Photo Credit: Public Domain

Oscar’s time at the Jersey Shore was similarly marred by ridicule, and he played the role as he had agreed to do—as the Aesthetic Movement’s fool.

Oscar Wilde at the Jersey Shore

Oscar spent five hectic days at the Jersey Shore lecturing on “The Decorative Arts” in Sea Bright, Long Branch, Asbury Park, Atlantic City, and Cape May. He traveled around resorts and sites — often in various places on the same day.

Regarding Oscar’s reception in the periodicals, it’s important to remember it was very fashionable for newspapers to mock Oscar — as was the intention of both the operetta and the lecture tour more broadly.

This gives a greater understanding of Oscar’s famous quote: “In the old days men had the rack. Now they have the Press.” By the time Oscar reached the Jersey Shore, he may have been a bit tired of the year-long criticism.

Sea Bright

On Monday, August 21st, Oscar gave a lecture at the Octagon Hotel in Sea Bright. According to the Sentinel, “he was very dreary and uninteresting putting many of his audience to sleep.”

This seems contradictory to the reporting of the Seabright Sentinel which reported that “A nurse girl at the Octagon became so frightened at Oscar Wilde that she ran away, and in doing so tumbled into an open cellarway and bruised herself severely.”

Newspapers never seemed to agree whether Oscar was too boring or too fascinating, either way, the press and gawkers indulged in heckling Oscar during his stay.

Long Branch

On Tuesday, August 22nd, 1882, Oscar lectured in Long Branch at the West End Hotel to a group of 400 people, mostly ladies, in the dining hall of the hotel while music played in nearby parlors. So there would be no confusion as to the subject matter, Oscar titled his lecture: “The Decorative Arts, and the Practical Application of the Principles of the Aesthetic Theory to Exterior and Interior House Decoration, with Observations Upon Dress and Personal Ornaments.”

According to The New York Herald, the audience indulged in stamping and derisive applause,” and “[Oscar’s] dress caused loud laughter among the same element of the audience…but nothing appeared to disturb his serenity.”

The Evansville Journal reports a more favorable reception: “When Oscar Wilde was at Long Branch, the other day, a great number of young ladies turned out and followed him through the promenade and everywhere about the beach.”

Meanwhile, The Cincinnati Post took jabs when reporting, “Oscar Wilde lectured at Long Branch the other day, and was snubbed and ridiculed by an audience composed largely of New York snobs. This was a good hint to Oscar that his mission to America was about ended, and that he had better pack up his sunflowers and old earthenware and go home.”

Asbury Park, Spring Lake, Atlantic City, + Cape May

Oscar was scheduled to lecture at Spring Lake but failed to appear — likely because a group of local boys hanged an effigy of Oscar from a flagpole, complete with corset, sunflower, knee-breeches, and Japanese parasol.

The following day, Oscar kept a low profile in Asbury Park, where he gave a lecture on “The Beautiful” at the Coleman House hotel. The Camden Daily Courier reported that “[Oscar] made himself scarce during the day, thereby evading the curiosity seekers and compelling those who desired to gaze upon his aesthetic countenance to pay the admission fee to the lecture.” Despite the negative press, more than 600 people showed up, clamoring to get a view of Oscar.

In Atlantic City, Oscar made himself so scarce, that it’s not known whether he even gave a lecture in Atlantic City at all.

In Cape May, Oscar entered the Stockton Hotel through a side door, and when departing Cape May, Oscar told an abusive crowd at the train station that they did not know how to behave. His celebrity had grown to such an extent that Oscar was accompanied by soldiers as he departed the Jersey Shore.

Aftermath + Legacy

In many ways, America made Oscar — or, rather, America gave Oscar the space and opportunity to invent himself. The whirlwind tour helped create the image of “Oscar Wilde” we conceive today.

First of all, Oscar only had long hair for one year of his life during this 1882 tour—because long hair was en vogue with those devoted to the Aesthetic Movement; yet most people still picture Oscar with long hair.

Secondly, it fortified Oscar’s character and artistic personality. When he first arrived, Oscar did little more than rehash popular tropes of the Aesthetic Movement, but by the time Oscar left, he had learned how to outmaneuver the press, how to address rooms of over 600 audience members, and how to cleverly and deftly deflect criticism.

See More: A List of North Jersey Slang Terms

It is largely due to Oscar’s successful reception in America that his first theatrical debuts occurred in New York, rather than London.

Though he suffered the slings and arrows of an unfavorable press and an often chiding public, Oscar got the last laugh. It was through the infamy of his tour that he arose like a Phoenix from the ashes to become a household name across America.

More Information about Oscar’s time in America can be found here, or on the podcast The Gilded Gentleman, Episode 51, “Whitman and Wilde Part 2: Oscar Wilde in New York, 1882.”